Rhythm is essential in human music and speech. Are we, however, the only mammals with a sense of rhythm? A team of researchers led by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen and the Seal centre Pieterburen show that seals can discriminate rhythm without prior training in an experimental study published in Biology Letters. The ability of seals to learn vocalisations may be linked to their rhythmic ability, which may have co-evolved in both humans and seals.

Why are we such talkative, musical creatures? Evolutionary biologists believe that our abilities for speech and music are related: Only animals that have the ability to learn new vocalisations, such as humans and songbirds, appear to have a sense of rhythm. “We know that our closest relatives, non-human primates, must be trained to respond to rhythm,” first author Laura Verga explains. “Even when trained, primates demonstrate very different rhythmic capacities than humans.” But what about other mammalian species?

Seal tempo

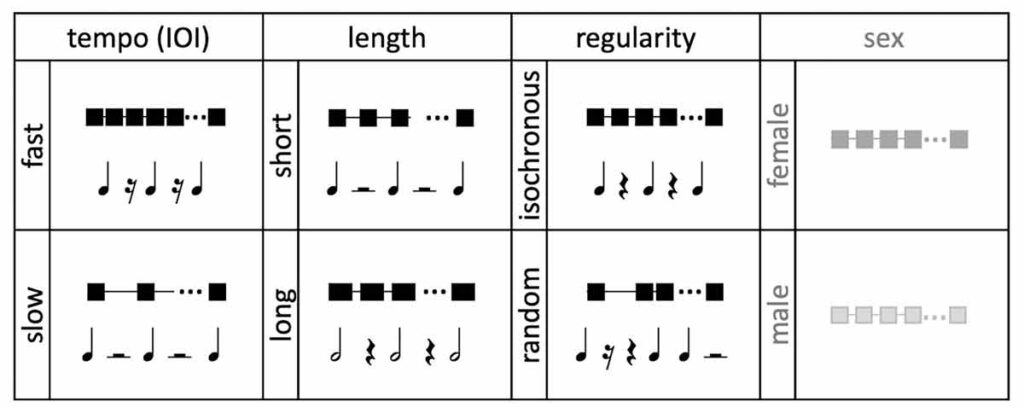

The researchers chose to test the rhythmic abilities of harbour seals, which are known to be vocal learners. The team began by recording sequences of seal vocalisations. The rhythmic properties of the sequences varied in three ways: tempo (fast or slow, like beats per minute in music), length (short or long, like the duration of musical notes), and regularity (regular or irregular, like a metronome vs. the rhythm of free jazz). Would these rhythmic patterns affect infant seals?

Twenty young seals were tested before being released into the wild at a rehabilitation centre (the Dutch Sealcentre Pieterburen). The team recorded how many times the seals turned their heads to look at the sound source using a method borrowed from human infant studies (behind their backs). This type of looking behaviour indicates whether animals (or infants) find a stimulus appealing. If seals can distinguish between different rhythmic properties, they may look longer or more frequently when they hear a preferred sequence.

When vocalizations were longer, faster, or rhythmically regular, the seals looked more frequently. This means that the 1-year-old seals spontaneously discriminated between regular (metronomic) and irregular (arrhythmic) sequences, sequences with short vs. long notes, and sequences with fast vs. slow tempos, without any training or rewards.

Origins in evolution

“Another mammal, other than us, exhibits rhythm processing and vocalisation learning,” Verga says. “This is a significant step forward in the debate over the evolutionary origins of human speech and musicality, both of which remain a mystery. Rhythm perception in seals emerges early in life, is robust, and does not require training or reinforcement, as it does in human babies.”

Next, Verga and her colleagues want to know if seals perceive rhythm in other animals’ vocalisations or even abstract sounds, and if other mammals have the same abilities: “Are seals special, or are other mammals also capable of spontaneously perceiving rhythm?”