A sunspot pointing toward Earth has the potential to cause solar flares, but experts told USA TODAY that this is far from unusual and that flares would have little effect on the Blue Planet.

AR3038, or Active Region 3038, has been expanding over the last week, according to Rob Steen burgh, acting director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Weather Forecast Office.

“That’s what sunspots do,” he explained. “They will, in general, grow over time. They go through stages before decaying.”

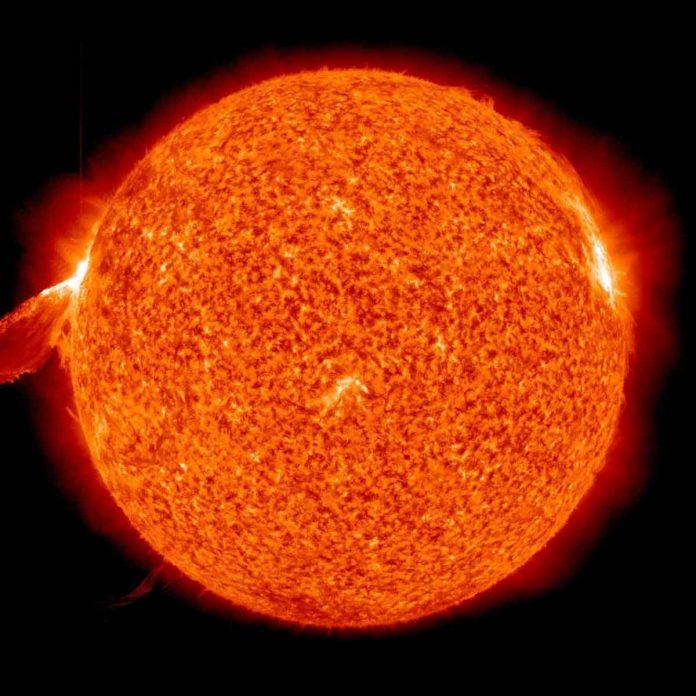

According to NASA, sunspots appear darker because they are cooler than other parts of the sun’s surface. Sunspots are cooler because they form where strong magnetic fields prevent heat from reaching the surface of the sun.

“I guess the simplest way to put it is that sunspots are magnetic activity regions,” Steenburgh explained.

According to NASA, solar flares are “a sudden explosion of energy caused by tangling, crossing, or reorganising of magnetic field lines near sunspots.”

“Think of it like twisting rubber bands,” Steenburgh explained. “If you have two rubber bands wrapped around your finger, they will eventually become too twisted and break. The difference between magnetic fields and electric fields is that they reconnect. And it is during this process that a flare is produced.”

The larger and more complex a sunspot becomes, the more likely solar flares are, according to Steenburgh.

C. Alex Young, associate director for science in NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s Heliophysics Science Division, said in an email that the sunspot has doubled in size every day for the past three days and is now about 2.5 times the size of Earth.

According to Young, the sunspot is producing small solar flares but “lacks the complexity for the largest flares.” There is a 30% chance the sunspot will produce medium-sized flares and a 10% chance it will produce large flares.

W. The sunspot, according to Dean Pesnell, project scientist at the Solar Dynamics Observatory, is a “modest-sized active region” that “has not grown abnormally rapidly and is still somewhat small in area.”

“AR 3038 is exactly the type of active region we would expect at this stage of the solar cycle,” he said.

According to Andrés Muoz-Jaramillo, lead scientist at the SouthWest Research Institute in San Antonio, the sunspot is nothing to be concerned about.

“I’d like to emphasise that there’s no need to panic,” he said. “They occur frequently, and we are prepared and doing everything possible to predict and mitigate their effects. For the most part, we don’t need to worry about it.”

Solar flares have different levels, according to Muoz-Jaramillo. A-class flares are the smallest, followed by B, C, M, and X at the highest strength. Within each letter class, there is a finer scale based on numbers, with higher numbers denoting greater intensity.

C flares are too weak to have an effect on Earth, according to Muoz-Jaramillo. More powerful M flares could disrupt radio communication at the Earth’s poles. At their worst, X flares can disrupt satellites, communication systems, and power grids, resulting in power shortages and outages.

Lower-intensity solar flares are fairly common, but X flares are less so, according to Steenburgh. He estimates that there are about 2,000 M1 flares, 175 X1 flares, and eight X10 flares in a single solar cycle, which lasts about 11 years. There are fewer than one large solar flare per cycle at X20 or higher. This solar cycle started in December of 2019.

According to Steen burgh, the AR3038 sunspot has caused C flares. Although there have been no M or X flares from this area, he believes more intense flares are possible in the coming week.