Two methods for reducing nest predation of vulnerable and endangered ground-nesting birds were tested using artificial nests. The study found that red foxes can be tricked into not eating bird eggs more easily than raccoon dogs. The methods could be used in conjunction with hunting to provide an alternative, non-lethal solution for protecting vulnerable prey.

Predator control is a common issue in areas where prey populations, such as ground-nesting waterfowl, are unable to withstand the impact of an increased predator population. For example, in areas where there are no apex predators, the red fox population can become excessively large for its native habitat. Furthermore, the red fox is an invasive species in some parts of the world. Foxes can cause a decline in the populations of prey species in both cases.

Predator control through hunting is time-consuming and cannot be done everywhere or at any time, such as during bird nesting season. As a result, there is a global need for non-lethal alternatives.

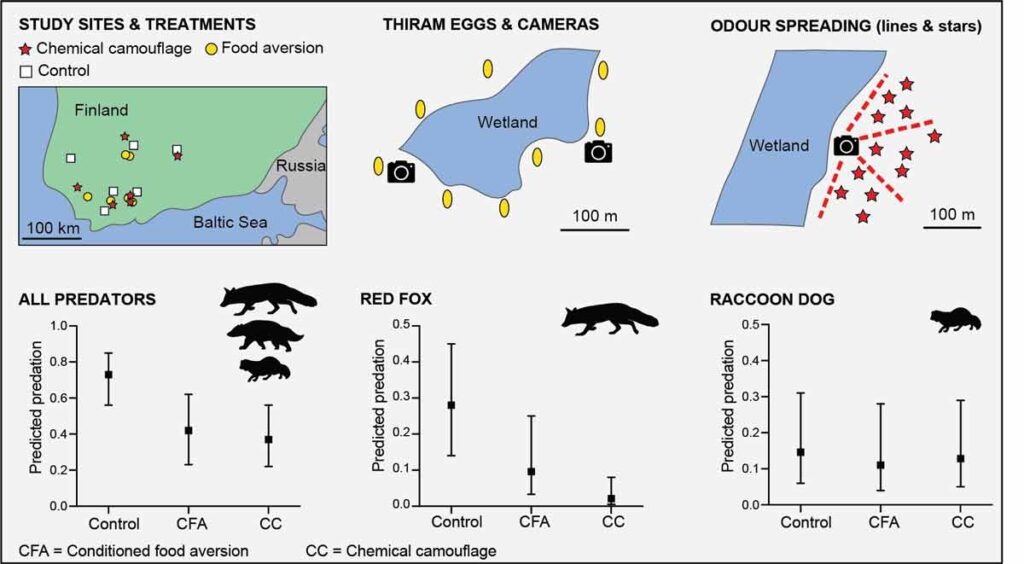

The international team of researchers tested two methods to reduce nest predation and thus protect the prey species in a large field experiment in southern Finland.

The researchers spread waterfowl odour in wetland areas at the first treatment sites. The researchers investigated whether high levels of prey odour in the area prevent predators from finding the artificial bird nests using chemical camouflage, a new method successfully tested in Australia and New Zealand.

In other areas, the researchers used eggs containing an aversive agent that causes nausea in order to train predators to believe that the bird eggs were inedible. For controlling a potential disturbance effect, the researchers also used control sites that they visited as frequently as the treatment sites.

The study found that chemical camouflage, in particular, reduced red fox predation on artificial waterfowl nests, but no such effect was found with raccoon dogs, a harmful invasive species in Finland.

“Red foxes may rely more on their sense of smell to find bird nests, whereas raccoon dogs may find the nests by chance when they move in the area,” says Vesa Selonen, Senior Researcher at the University of Turku in Finland.

The results with the eggs containing an aversive agent were similar but less clear.

“However, our findings are intriguing because they suggest that these methods could reduce nest predation of vulnerable and endangered waterfowl species. Next, we need to investigate whether the results we observed with the artificial nests can also lead to the preservation of real bird nests and, as a result, a greater number of young birds,” says University of Turku Professor of Ecology Toni Laaksonen. The study was published in the journal Biological Conservation.