Today’s marine giants are blue and humpback whales. They routinely make massive migrations across the ocean to breed and give birth in waters where predators are scarce.

New research from a team of scientists led by researchers from the University of Utah, Smithsonian Institution, Vanderbilt University, University of Nevada, Reno, University of Edinburgh, University of Texas at Austin, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, and the University of Oxford suggests that nearly 200 million years before school bus-sized marine reptiles known as ichthyosaurs may have been making similar migrations to breed and give birth together.

The findings were published today in the journal Current Biology. The study examined a rich fossil bed in the renowned Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park (BISP) in Nevada’s Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest. There many 50-foot-long ichthyosaurs (Shonisaurus popularis) lay petrified in stone.

The study offers a plausible explanation as to how at least 37 of these marine reptiles came to meet their ends in the same locality. This is a question that has vexed palaeontologists for more than half a century.

Some palaeontologists have proposed that BISP’s ichthyosaurs have been adopted as Nevada’s state fossil. They died in a mass stranding event similar to those that occasionally afflict modern whales. Or maybe the creatures were poisoned by toxins such as those found in a nearby harmful algal bloom. The problem is that these hypotheses are not supported by strong lines of scientific evidence.

To try to solve this prehistoric mystery, scientists combined newer paleontological techniques like 3D scanning and geochemistry with traditional paleontological perseverance. They combined archival materials, photographs, maps, field notes, and drawer after drawer of museum collections for shreds of evidence that could be re-analyzed.

Most well-studied paleontological sites excavate fossils so that scientists at research institutions can study them more closely. The main attraction for visitors to the Nevada State Park-run BISP is a barn-like building that houses Quarry 2. It is an array of ichthyosaurs that have been left embedded in the rock for the public to see and appreciate. Quarry 2 contains partial skeletons of an estimated seven different ichthyosaurs. All of these appear to have died around the same time.

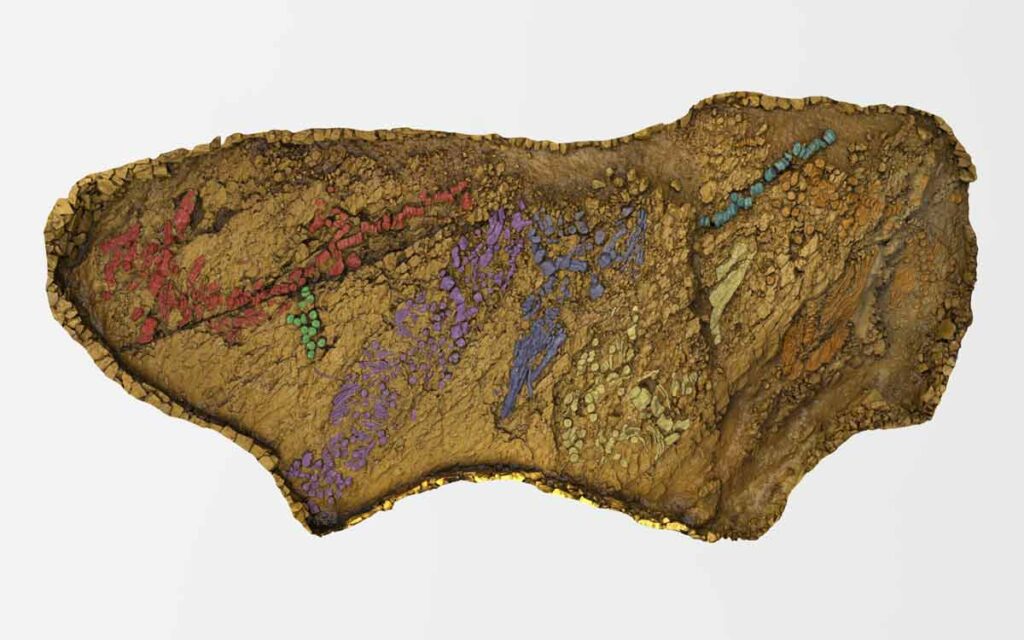

The palaeontologists measured bones and studied the site using traditional paleontological techniques. Scientists took hundreds of photographs and millions of point measurements. Then they stitched these together using specialised software to create a 3D model of the fossil bed.

The team collected tiny samples of the rock surrounding the fossils. They performed a series of geochemical tests to look for signs of environmental disturbance. One test measured mercury and found no significantly increased levels.

Other tests examined different types of carbon and determined that there was no evidence of sudden increases in organic matter in the marine sediments that would result in a dearth of oxygen in the surrounding waters.

These geochemical tests found no evidence that these ichthyosaurs died as a result of a cataclysm. It would have severely disrupted the ecosystem in which they died. The research team continued to look beyond Quarry 2 to the surrounding geology and all of the previously excavated fossils.

The geologic evidence indicates that when the ichthyosaurs died, their bones eventually sank to the bottom of the sea. The area’s limestone and mudstone were chock-full of large adult Shonisaurus specimens. But other marine vertebrates were scarce. The bulk of the other fossils at BISP come from small invertebrates such as clams and ammonites.

The paleontological dragnet had eliminated some of the potential causes of death. It was beginning to provide intriguing clues about the type of ecosystem these marine predators were swimming in. But the evidence still did not clearly point to an alternative explanation.

The term “responsibility” refers to the act of determining whether or not a person is responsible for his or her own actions. Careful comparison of the bones and teeth using micro-CT X-ray scans at Vanderbilt University revealed that these small bones were in fact embryonic and newborn Shonisaurus.

Further examination of the strata in which the various clusters of ichthyosaur bones were discovered. It revealed that the ages of the many BISP fossil beds were separated by hundreds of thousands of years.

The next step in this line of research is to investigate other ichthyosaur and Shonisaurus sites in North America. The scientists want to begin to recreate their ancient world by looking for other breeding sites or places with greater diversity of other species that could have been rich feeding grounds for this extinct apex predator.

The 3D scans of the site are now available for other researchers to study as well as the general public to explore via the open-source Smithsonian’s Voyager platform.